git:Intermediate

How to Undo State

reset

The reset command will reset the current state of HEAD to the location that you set. The flag you specify will determine how destructive the command will be.

$ git reset --soft @^ # resets the HEAD to the specified commit, but leaves the working directory and staging area unchanged$ git reset --mixed @^ # default: resets HEAD to the specified commit, but the files in the working directory arent changed$ git reset --hard @^ # "delete" the current commit: reset HEAD to the specified commit, and clear any other changes that were in the working directory or staging arearestore

The restore command will default to restoring the working directory to the current state of HEAD. It will restore the current state of the working directory to the commit that you specify.

You can specify a specific file, a directory, or :/, which refers to all tracked files

--staged flag

This flag is really useful if you want to remove a file from the staging area, but want to keep the changes in the working directory.

revert

revert is a little bit different than the other two commands. The other two commands allow you to move/reset the state of HEAD; revert will create a new commit which contains the changes that will undo the changes done in the specified commits.

This is most used when you have already pushed the commits to a remote repo. You wouldn’t want to delete a commit or forcibly move a branch location because that might mess with other peoples commit history. This preserves the history but undoes the change.

Handling Commits

interactive rebase

rebasing was mentioned in the last lesson: its just a way of moving commits to be on top of another branch, to keep a more linear history. Interactive rebase provides you with a couple more options, and lets you decide what action you make on each commit.

This is generally used to squash commits: all that means is you put all the changes from the selected commit, into the previous commit

An example of using this command might be:

$ git rebase -i @^^^ # allows you to modify or squash the last 3 commitsOther common changes that you can perform are:

- pick: use this commit

- reword: use this commit, but change the message

- edit: use this commit, but edit it first

- squash: use this commit, but meld it into the previous commit

All of these operations, their summaries, and many other available commands come up when running the interactive

rebasecommand

reflog

reflog is a git command, but it also refers to a data store used to record every time the tips of branches and other refs (such as HEAD) are updated.

Commit data is almost never deleted, so the reflog allows you to undo any changes, like a git reset --hard @^, or git rebase that squashed commits.

An example animation of how you might use the reflog:

And a real world interaction with a git repo:

Alternatively, you can add the flag --reflog to git log to get a combined output:

$ git log --reflog # to view the commit logs intertwined$ git log --graph --oneline --reflog # to get a more visual, graph-like viewdangling commits

A dangling commit is just a commit that has no easy way of being referenced. If it exists in the log heirarchy of some branch, tag, or HEAD; you can git log and easily find the commit; these commits would not be considered dangling. An example of a dangling commit would be the commit that was deleted in the previous animation, which we could only refer to via the reflog.

This is just terminology, but it comes up quite frequently

Managing files

.gitignore files

These are really important for keeping clutter out of your git directory that doesn’t need to be committed. These files allow you to declare that you never want to add certain files to your staging area (and therefore never be committed)

Important syntax includes:\

**: match any number of prefixed directories in this project\*: wildcard character that matches 0 or more characters\!: negate any previous ignore statements that would have removed this pattern\[0-9]: a group of characters, any of which match

a .gitignore file might have entries that look like the following

node_modules/ # all files in the node_modules directory*.o # all files that end with a .o extension. Usually compiled intermediary files**/logs # any directory, anywhere in the repo, called "logs"!important.log # I want to make sure to _not_ ignore this fileWhen making a new repo, GitHub will often ask if you would like to immediately add a .gitignore file to the repo, depending on the type of language you are working in.

If you are familiar with using npm (node package manager), you will have all your dependencies in a node_modules/ file; this is unnecessary, as they can all be cloned later so long as you have the package.json file declaring all the dependencies

You can read more about them here

stashing changes

The command git stash allows you create something like a commit, but not really. It saves, and then undoes any uncommitted changes stashing them for later use.

Useful tools

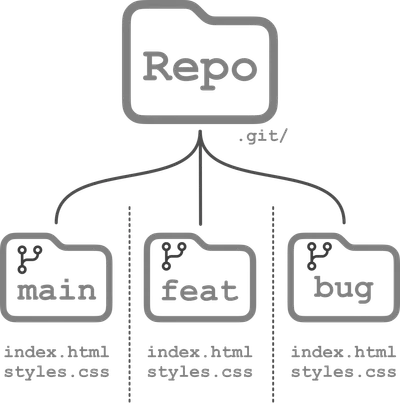

worktrees

Worktrees enable you to have multiple branches active at once; you can essentially have multiple working directories active at once, in their own separate directories within your local repo.

This is really nice when, for example, you are working on a feature that isnt finished yet and then get an urgent bug report.

The basic use cases for worktrees include:

$ git worktree add {new-dir-path} {commit-ish} # Create a new directory that houses the specified branch$ git worktree remove {worktree} # Remove the directory with the worktreeTo learn a little bit more about worktrees and how I use them, you can check out a video that I made on this topic.

patch commits

Patch commits are just a fancy way of saying, “Pick out the parts/patchs from the file that I want to include in this commit, and leave the other parts out of the staging area.”

You can enter patch commit mode by adding the --patch flag, when using git add or git commit

$ git add --patch [path] ...$ git commit --patch [-m {message}] ...Some of the available options when patch-adding are:

- y: add the referenced hunk to the staging area / commit

- n: do not add the referenced hunk to the staging area / commit

- e: edit the hunk to select only the desired lines to add too the staging area / commit

This is useful when you have made multiple modifications in a file, but they belong in two or more commits to make logical sense; you would separate them to make your intent clear.

cherry-picking

cherry-picking does exactly what it sounds like it should. It allows you to select a specific commit and apply it onto the tip of your HEAD. This is useful to get a commit that has an urgent change over from a branch and into another one without having to go through the process of merging the changes associated with every other commit.

When dealing with cherry-picking, it is important to remember how commits are stored. Commits store hashes of entire files (blobs); if we just moved that commit over, we would be moving over the snapshot of that file, effectively overwriting the changes on our current branch. Instead, cherry-picking creates a diff between the current selected commit, and its parent, and then applies those changes into a new commit, which it places at our HEAD.

bisect

bisect allows you walk through a section of your commits using binary search, to try and isolate where a certain (usually breaking or bug inducing) change was made.

$ git bisect start <known bad commit-ish> <known good commit-ish> # define the bounds for the binary searching to occur$ git bisect good|bad # mark the current commit as good or bad to perform a binary search split$ git bisect log # show the bisect stateWhen you are performing a bisect, you check out each commit individually, allowing you to perform some build step like make or other such test to figure out exactly where a bug was introduced.

Hooks

A git hook is just a script that runs when git sees a specific event has been triggered. One such example is right before a commit occurs (pre-commit)

A git hook is just a shell script with a special name that git looks for in .git/hooks/. All available hook actions match up with files that are already in the folder; to activate one of these actions, just remove the .sample suffix.

Here is an example of a hook that I wrote to enforce go fmt on all committed files prior to the commit:

### pre-commit

#!/bin/sh

STAGED_GO_FILES=$(git diff --cached --name-only | grep ".go$")if [ "$STAGED_GO_FILES" = "" ]; then exit 0fi

PASS=true

for FILE in $STAGED_GO_FILESdo go fmt $FILE if [ $? != 0 ]; then PASS=false fi

git add $FILEdone

if ! $PASS; then printf "COMMIT FAILED\n" exit 1else printf "COMMIT SUCCEEDED\n"fi

exit 0Common uses for hooks include:

- Running a code formatter over your code

- Building your project using the state of the proposed commit to make sure that it works

- Ensuring your commit message match a certain format

Usually tools/packages, such as husky, are used to abstract over writing shell scripts for this.

difftool

various tools have been made to provide a fancy front-ends for git diff; these are called difftools. These are nice when you are performing a complicated merge with lots of conflicts as they let you view the code a bit more naturally.

Some of the most common ones are VSCode and meld

Limiting repo size

Both git partial clone and git sparse-checkout are viable options to limit the size of the repo on your machine. One really common example is with the use of Mono-repos in industry. As a developer, you dont need all 2 million files for all micro-services, you only need the one directory that contains the project you are working on. Reducing the directory size will significantly speed up common commands like git status, which need to

Partial clone

We recently talked about how git stores commit data in trees and blobs. When working in really large repos with 100s of GB of data, cloning that can take hours or days. Git provides a way to clone only the metadata, such as the commit messages and commit lineage, without downloading other file contents. When you do eventually need a file to work on, git will request it from the server in a JIT (Just In Time) fashion, limiting the upfront cloning cost and amortizing the requests.

You can do so with the --filter flag when cloning

$ git clone --filter=blob:none <link> # dont download any file blobs$ git clone --filter=blob:limit=<n>[kmg] # git clone --filter=blob:limit=1k limits downloads of blobs larger than a kilobyte$ git clone --filter=object:type=(tag|commit|tree|blob) # omit all objects that are not of the requested type$ git clone --filter=... --filter=... # you can provide multiple filters, but only objects that match _both_ will be clonedYou can find a documentation on all possible filter-spec options here.

Sparse checkout

Sparse checkout allows you to select only specific files or directories to be included in your working directory. When passing in the --sparse flag, only the files in the root of the directory are checked out by default. The files in the working directory can be updated later with the git sparse-checkout command.

$ git clone --sparse git@github.com:jtledon/repo.git # enable sparse-checkout and only include the root files by default$ git sparse-checkout add|set website/backend/api/ # add the files located at website/backend/api to the working directoryYou can also pass the --no-cone options and pass in patterns rather than directory and file locations. These patterns follow the same syntax as .gitignores.

$ git sparse-checkout set --no-cone '/*' '!**/logs' # include everything except for any logs directoriesYou can read more about how to use these features here or watch a brief tutorial here.

Combining them

Sparse checkout and partial clone can work in conjunction with one another to make a speedy git experience on even the largest repos.

# only include the root files, and only download file blob data as its needed$ git clone --filter=blob:none --sparse git@github.com:jtledon/repo.git$ git sparse-checkout add|set website/backend/api/Submodules

There are times when you need to include other git repositories within your current git repo so that you can use it in your project. You still want to be able to pull from those repos, but dont want your parent git project to track those files. This is the usecase for git submodules.

$ git submodule add repository_url [path] # add a new submodule to your repo$ git submodule foreach git pullThe settings and config for submodules can be found in the .gitmodules file.

If you are cloning a repo that has submodules within it:

$ git clone --recurse-submodules # follow all recursive submodules and clone them all$ git clone --shallow-submodules # only clone submodules to a depth of 1If your repo has submodules within it, but you forgot to clone it using --recurse-submodules:

$ git submodule update --init --recursive # initialize your repo as using submodules and clone them in recursivelyHomework

This weeks homework is going to be a little bit more in depth. You will need to record a video of yourself:

- Using

restoreto remove a file from your staging area without undoing the file contents - Making a commit

- Pushing to your own remote repo made on GitHub

git reset --hard @^over the commit you just made and pushed- Showing the diff between your local branch, and the remote branch you just pushed to

- Getting the deleted commit back using the reflog and updating your branch to point at it

And email it to me with the title like: “[98172] HW2”. Ideally, the video with be 2 minutes or less